Those are some of the words to an old Tom Lehrer song.

He was a mathematician at Harvard University, who for several years in the Sixties also wrote songs, including what he suggests would have been a more appropriate fight song for Harvard. ("Demonstrate to them our skill! Albeit they possess the might, nonetheless we have the will! Oh, we shall fight for Harvard's glorious name; won't it be peachy if we win the game? Oh, goody. Hurl that spheroid down the field, and fight! Fight! Fight!")

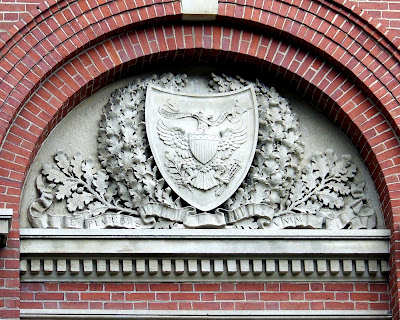

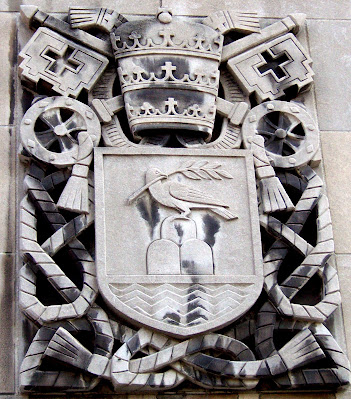

Anyway, we were staying at a B&B in Cambridge, and had the opportunity over several days to stroll across and around the Harvard University campus. I've already shown you some of the arms that appear there in my last couple of posts: the arms of the United States, and those of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Well, today we're going to look at some of the depictions of the arms of the University itself, scattered here and there about the campus.

A blazon, I suppose, would be: Gules three open books argent bound and clasped or thereon the word VE RI TAS sable, if you keep in mind that the "gules" they use is often more of a "maroon" than a true "red". (This is not to say that you can't find a lot of depictions of the arms with red, only that you more often see it as a darker blood-red or maroon, like on the cap and tee shirt I bought there with the arms on them.)

Anyway, with all that as background, here are images of some of the coat of arms of Harvard University found on the campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Over a doorway, flanked by the arms of the State of New York (left) and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (right):

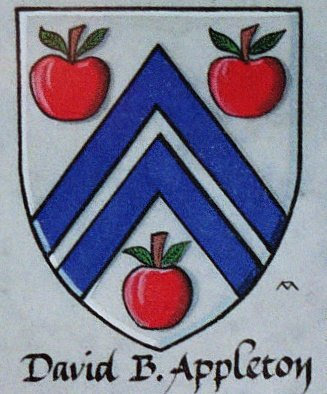

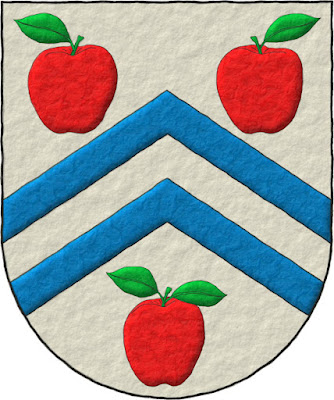

In addition, there were a couple of versions harking back to Harvard's early years as a school of divinity in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, where it was used on the college seal in 1650 and thence up until about 1800. These versions have a chevron between the three books, the upper two of which are face up, and the lower one of which is aversant (which can be seen best in the lower image). The upward facing books symbolize the truth that is discernible through our five senses; the overturned book symbolizes that which can only be known through the illumination of the Holy Spirit.

.jpg)

.tif)

.JPG)