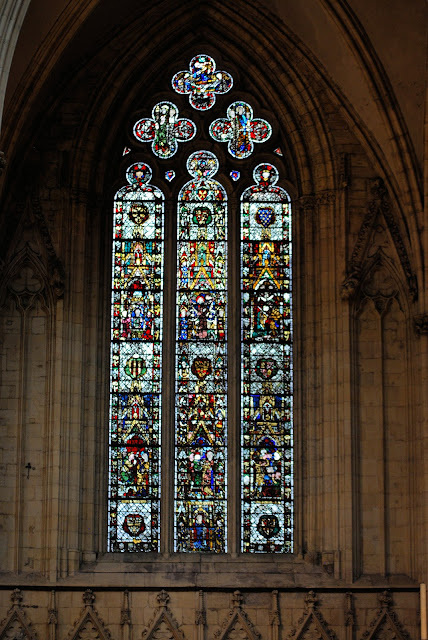

Continuing our review of the armorial windows all based on the same overall pattern in York Minster, we now come to the following:

Here again in the five main lights we have a row of Biblical scenes and underneath them a row of coats of arms.

Morrell (sometimes Morrill*), Azure on a cross argent a lion rampant gules; Fitz-Ranulph, Per fess indented or and azure; England (as we keep seeing in the central position), Gules three lions passant guardant in pale or; Neville, Gules a saltire argent); and Fitz-Alan, Gules a lion rampant or.

In the next window,

In the next window,

we have the same overall pattern with different coats of arms (well, except for England!):

Here, we have a little more difficulty in properly identifying a couple of these arms. From left to right, we have:

Here, we have a little more difficulty in properly identifying a couple of these arms. From left to right, we have:

[Unknown], Sable a cross patonce or. Papworth; Ordinary of British Armorials lists eleven different families with these arms, and the Dictionary of British Arms gives us for this same coat: Alverthorp, Braham, Brame, Delafeld, Goldebroow, Herland, Holand/Holland, Hoyland, Lascelles, Massy/Massey, Pulford, and Warde, so I can't even make a good guess at this time;

Dacre [probably], Gules three escallops argent. Burke’s General Armory says Dacre is Gules three escallops or. But the Dictionary of British Arms says those arms belong to Chamberlain, Dumaresque, and Palmer, while citing plenty of Dacre/Dacres with the silver escallops;

England, Gules three lions passant guardant in pale or;

Percy ancient, Azure five fusils conjoined in fess or; and

Richard, Earl of Cornwall, Argent a lion rampant gules crowned or within a bordure sable semy of bezants. (The glasswork on the bordure here is not up to the same level as the rest of the shield. It's hard to tell the difference here from the blazoned bordure sable semy of bezants and a bordure or. Feel free to click on the image above to go to the full-size photograph to better see what I mean.)

Difficulties of identification aside, these are some lovely armorial windows, aren't they?

* Papworth's Dictionary of British Amorials spells it Morrill; Burke's General Armory spells it Morrell. Frankly, it's pretty much "six of one, half a dozen of the other." Shakespeare spelled his own surname in several different ways, sometimes in the same document. And in my own family history, one of my ancestors whose surname is normally spelled Bigelow, has variants in different contemporary documents running the full range from Biglo to Biggalough. Anyway, this I to E switch seems like nothing at all under the circumstances.

.jpg)